In the Money Podcast with Amber Kanwar

Last week, I had the pleasure of joining Amber Kanwar on the In the Money podcast.

In this episode, we discuss how Optimist Fund capitalized on market fear and volatility in 2022 to drive strong long-term returns.

Our approach remains the same—leveraging periods of uncertainty to maximize investment performance over time.

We also took a deep dive into a few of our top holdings and why we believe they are well-positioned to generate strong returns over the next five years.

Click the image below to listen to the full interview.

Capital Compounders Podcast

Last month I was interviewed on the Capital Compounders Show hosted by Robin Speziale.

In this conversation, Robin and I discussed our investment philosophy centered on ambitious, growth-oriented companies, as well as my personal journey from sports to investing, the challenges faced in launching Optimist, and the importance of unit economics in evaluating businesses.

The discussion also covers specific companies like Carvana, Uber, DoorDash, HelloFresh, Wayfair, Latham Group, and the unique business model of ThredUp.

Click the link below to listen to the full interview.

The Global Food Fight: How Valuable Can Food Delivery Leaders Become? (Part 3/3)

The growth opportunity is enormous.

Online food and grocery delivery remains under 15% penetrated across all developed markets. As much as the industry has exploded over the last 5 years, we believe we remain in the early innings.

GMV = Gross Merchandise Volume

US food delivery and online grocery penetration is around 10% today. Over the next 10 years, we believe food delivery platforms can penetrate 30% of industry spend and online grocery can reach 35% penetration underpinning mid-teens revenue growth in both categories.

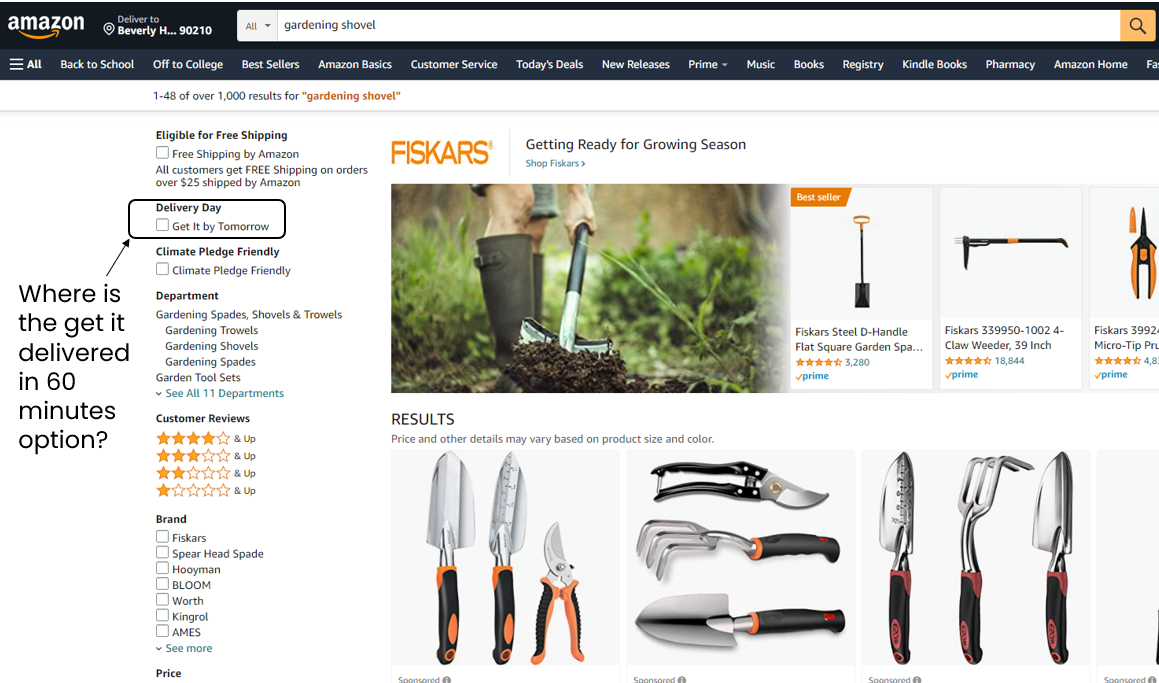

Online on-demand commerce in non-food categories is under 1% penetrated.

Total US sales of general merchandise categories such as clothing, home furnishings, electronics, sporting goods, and office supplies totals ~$1.5 trillion annually. Today we believe that under $5B worth of goods in these categories would be delivered in under 2 hours. A mere 2% penetration rate would drive significant growth for on-demand commerce platforms given the size of the market. This market presents significant opportunity, but time will tell if under 2 hour delivery in categories beyond food and convenience store items really takes off.

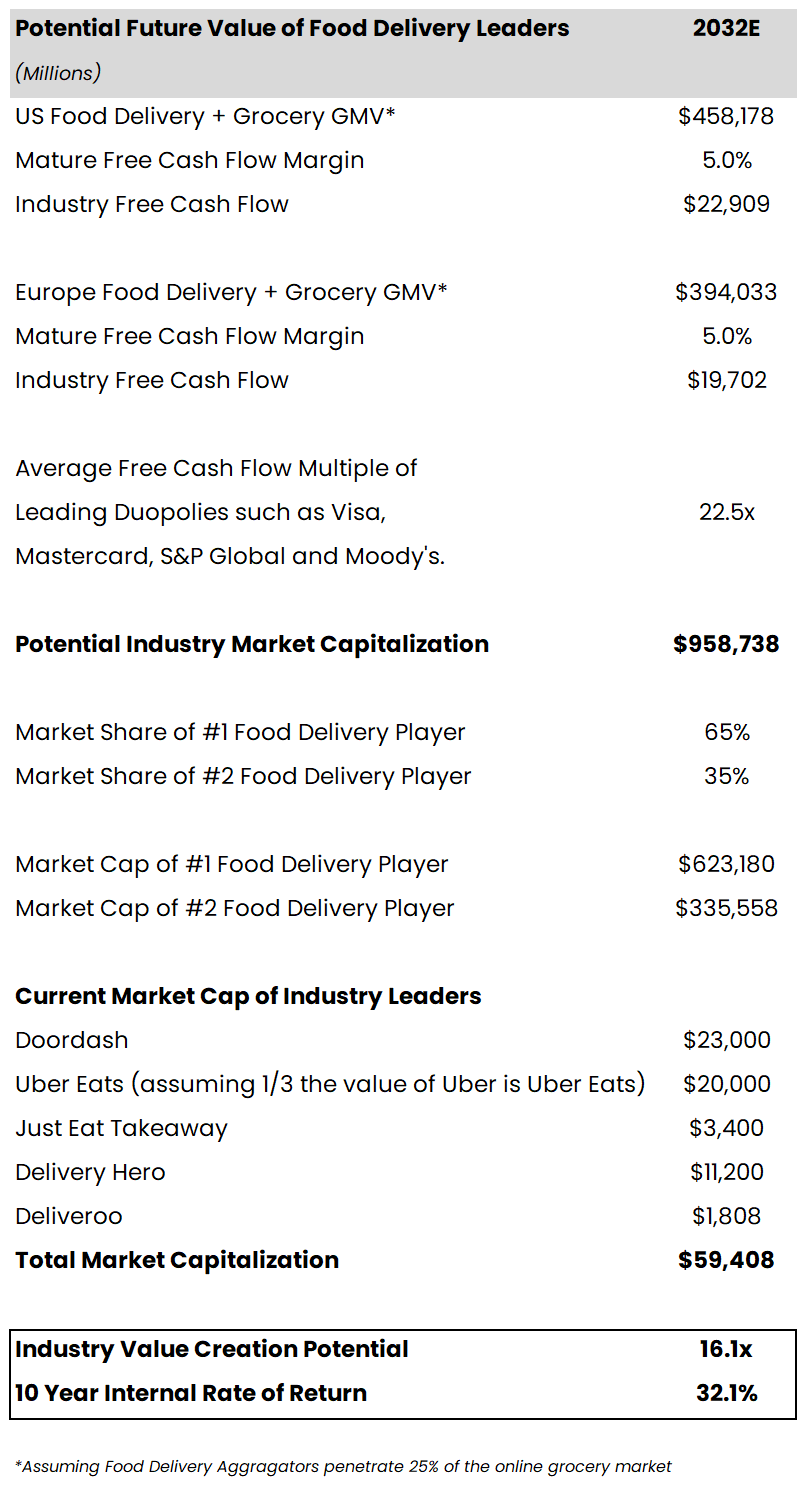

We believe the aggregate market capitalization of the food delivery industry in North America and Europe can approach $1 trillion in the next decade.

Source: Optimist Fund Estimate, Statista, Company Filings, fred.stlouisfed.org

As at: September 22, 2022

Based on only the core restaurant and grocery opportunity, we believe the food delivery aggregator industry will support close to a trillion dollars in market capitalization in 10 years. This does not include other retail verticals or other adjacent opportunities that will unfold over time.

By sizing the opportunity, it makes sense why companies in the space have invested so aggressively in attempts to win.

The size of the prize is definitely worth the fight.

Today Optimist Fund own’s Uber, Doordash and Just Eat Takeaway. We will discuss each of these holdings in more detail in future commentary.

The Global Food Fight: Food Delivery 2.0 (Part 2/3)

Third party delivery services changed the food delivery landscape.

Between 2011 and 2015, three-sided food delivery marketplaces were founded such as Doordash, Uber Eats, Postmates (which was acquired by Uber in 2020) and Deliveroo(UK based). The three sides to the marketplace were consumers, restaurants, and delivery drivers.

In food delivery 1.0 the delivery driver worked for the restaurant. In food delivery 2.0 the delivery driver is an independent contractor recruited by the three sided marketplace. Food delivery 2.0 marketplaces recognized that consumers wanted to order delivery from restaurants that didn’t deliver. They went to some of those restaurants and asked if their online marketplace enabled the restaurant to receive delivery orders and took care of the delivery would the restaurant be interested in paying the food delivery 2.0 marketplace a commission for those orders? Restaurants reacted favorably to the idea as they viewed it as a way to drive incremental orders to their business. This changed the food delivery landscape.

7 years ago, if someone decided they wanted to order in, they might open their Grubhub app (in the US) and see options from hundreds of independent restaurants but the biggest restaurants that everyone knows such as McDonalds, Wendy’s and Burger King were nowhere to be found. If the customer really wanted Wendy’s, they might go to google and search for Wendy’s delivery. Then the first link in the search results would appear as “Order Wendy’s delivery on Doordash”.

Doordash aggressively added every restaurant they could to their marketplace with an emphasis on suburban markets where few delivery options existed. Doordash was so adamant about accumulating all the major restaurant supply on their network that even if Wendy’s directly told Doordash they did not want to partner, Doordash would load their menu on their marketplace manually, mark up the prices and if a consumer ordered something from Wendy’s, instead of that order being sent to Wendy’s to be ready for pickup, as would be typical, a Doordash driver would stand in line and order the food for the customer.

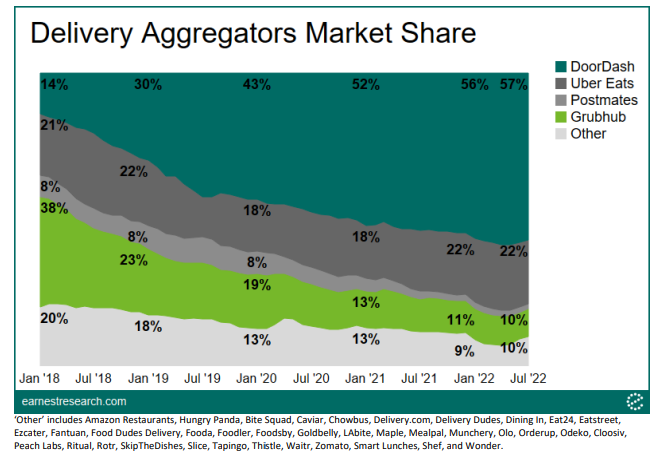

Over the last 5 years, DoorDash’s US market share went from ~15% to ~60% today. The important context for this data is that Doordash didn’t gain all their market share from Grubhub. It was driven by the food delivery market growing the fastest in the suburban markets where Doordash was already the leader and Grubhub was largely non existent. Doordash was the leading food delivery player in the most nascent markets (the suburbs) and Grubhub was the leading food delivery player in the most mature food delivery markets (urban areas like Manhattan, Chicago, and Philadelphia). As the most nascent suburban markets continued to grow at rapid rates, DoorDash ended up significantly larger than every other player in the US.

Source: earnestresearch.com

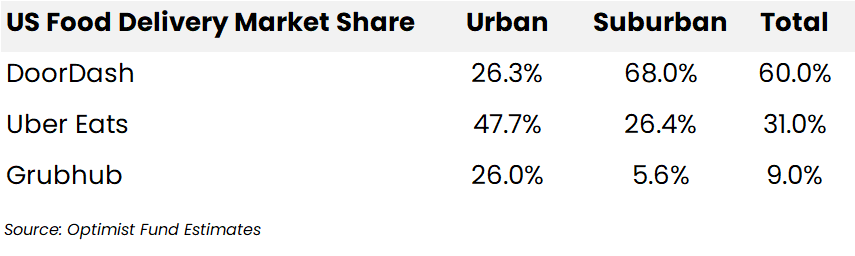

National market share data is helpful in understanding the scale of each food delivery business, but the composition of that market share throughout the country is an important nuance. 57% share in every region would have different implications than 100% share in 57% of the country. The underlying composition that aggregates to the national numbers has important takeaways.

DoorDash’s food delivery business is even more attractive then their national market share suggests. We believe their dominant position in the suburbs is the hardest to replicate and has the most significant future growth opportunity.

There are 331 cities in the United States with a population of more than 100,000 people that in aggregate make up 30% of the US population. The work to sign up all the restaurant supply in every city with 20,000 people is substantial. On top of that, Uber Eats doesn’t have the benefit of a significant rideshare business in these small cities/towns that provides them with driver supply and a brand to leverage. This makes catching DoorDash in the suburbs extremely difficult.

According to Edison trends in 2020, tier 1 cities which account for 6% of the US population accounted for 36% of the food delivery sales. In other words, the average person in tier 1 cities spend 9x the amount on food delivery than the 94% of Americans that don’t live in tier 1 cities. This makes sense as the number of food delivery options available to people outside of tier 1 cities was limited prior to DoorDash. We believe over time food delivery sales will be more in line with population distribution which should drive superior growth in the suburbs for years to come.

Food delivery 1.0 marketplaces were reluctant to offer their own logistics service which in hindsight was a mistake.

In the 2011-2015 time frame most of the public food delivery companies were focused on scaling market leadership and profitability of their core food delivery 1.0 businesses. Entering the logistics business would’ve pushed out their ability to scale margins for 8-10 years. Building an on-demand logistics network for restaurants is initially loss making until reaching a sufficient local scale and maturity. Reaching maturity across an entire country is a 10+ year journey making it a material decision that has significant implications to the financial profile of the business.

But, as the food delivery 2.0 marketplaces continued to grow rapidly, food delivery 1.0 marketplaces realized it was a business they needed to enter. They described the strategic pivot as the creation of hybrid marketplaces. One platform with all the old delivery restaurants and all the restaurants that never offered delivery.

In 2015, Grubhub launched their logistics offering which at the time was highly controversial. A year later, Takeaway.com (a predecessor to Just Eat Takeaway) launched their logistics service in a few cities in the Netherlands. Just Eat (which later merged with Takeaway.com to form Just Eat Takeaway) finally entered logistics through an acquisition of SkiptheDishes, a Canadian company, in late 2016.

Each food delivery 1.0 player invested in building out a food delivery 2.0 business to become a hybrid marketplace. Managing this transition was difficult. They needed to invest to build a logistics offering while not investing too much to significantly aggravate their existing public market investors that wanted the business to generate profits. This balancing act gave Doordash, Uber Eats, and every other food delivery 2.0 player a window of opportunity to gain meaningful market share.

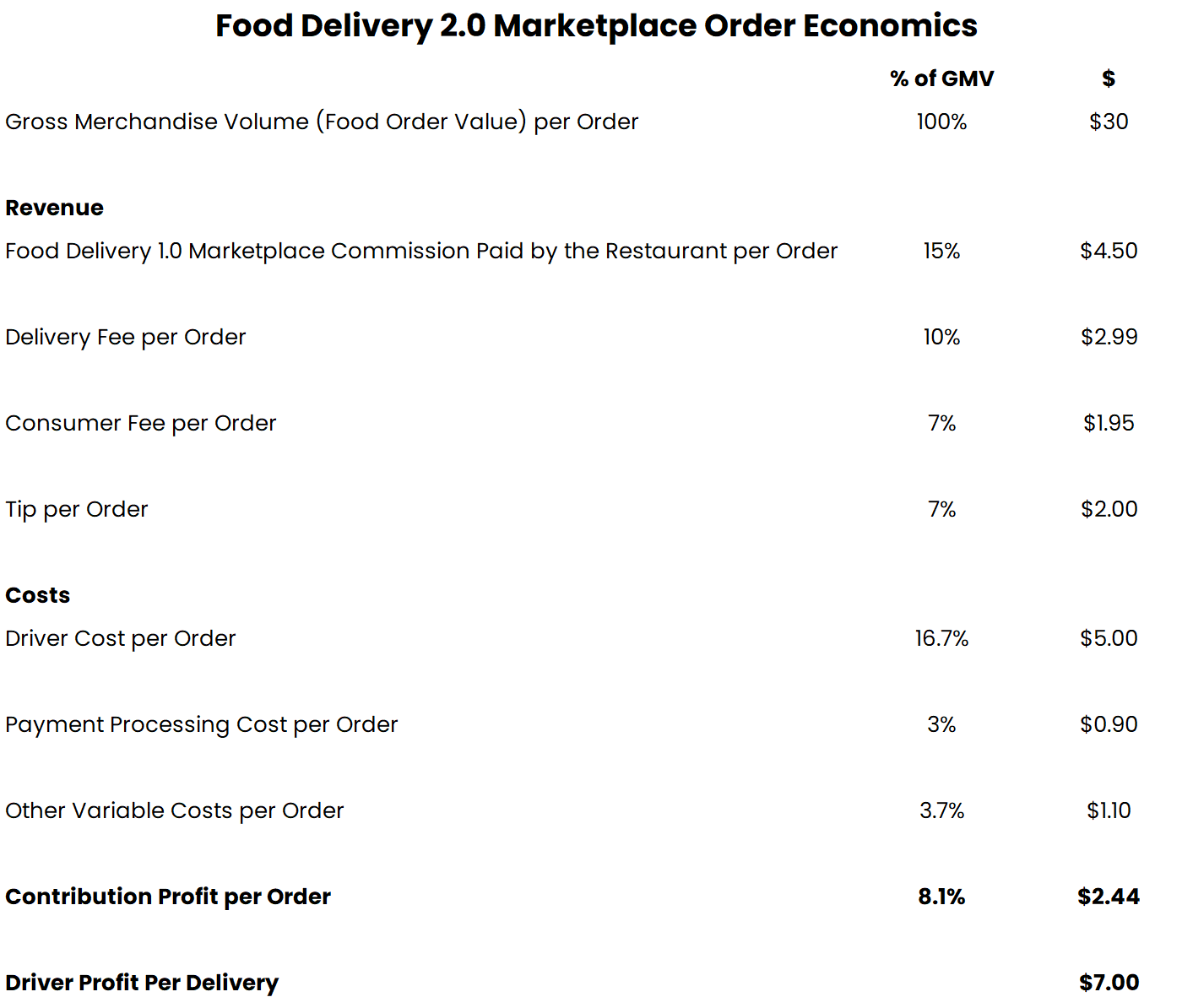

The economics of food delivery 2.0 orders are comparable to food delivery 1.0 orders at maturity.

Delivery 2.0 orders overtime are on par with the economics of food delivery 1.0 orders but initially they are not profitable. The reason for this is the challenge of balancing supply and demand between consumers and delivery drivers. Offering food delivery for McDonalds requires a fair amount of drivers before marketing to consumers that they can order McDonalds to their house. If 100 people want to buy a Big Mac in 45 minutes and the delivery service has 1 driver, customers will be disappointed with the service. If consumers expect their order to come in 45 minutes and it comes in 5 hours, they are mad at Doordash, not McDonalds.

Food delivery 2.0 marketplaces need to scale supply at the same time they scale demand to keep consumers and drivers happy. It is very difficult to do this without over compensating drivers and consumers in the early days.

Source: Optimist Fund Estimates, Company Filings

As you can see the order economics for food delivery 2.0 marketplaces net out to a similar amount at maturity but more costs need to be considered since the marketplace is handling the delivery.

When first launching a delivery service in a neighborhood the order economics look much different. Commission rates are often lower, and the driver cost per order is often higher than in the example above.

First lets address the lower commission rates. Signing an exclusive agreement with a popular chain like McDonalds is a quick way to get a significant amount of orders quickly. Attracting McDonalds customers to download your food delivery platform will help convince other restaurants in the area to sign up to the platform as well. Since McDonalds understands the value they bring to a food delivery platform they are able to negotiate lower commission rates. The food delivery business might be willing to lose money on every McDonalds order because it results in making more money on future orders from other restaurants on the platform.

Since food delivery 2.0 marketplaces are on-demand platforms, they need drivers before they receive orders. To build driver supply they must offer higher incentives. This could be a $5 per order bonus on top of the $5 per order payment we already have in the above example. They must overcompensate drivers to ensure they have the driver supply to create a positive consumer experience.

By incorporating both of these additional costs, it’s easy to see how order economics can be unprofitable at the onset. Furthermore, this isn’t even including the advertising expense required to raise brand awareness and acquire customers. Food delivery 2.0 marketplaces are exceptionally difficult and costly to build.

Source: 2022 Uber Investor Day Presentation

Scaled food delivery businesses (whether 1.0 or 2.0 or hybrid) are highly profitable businesses that are extremely difficult to build.

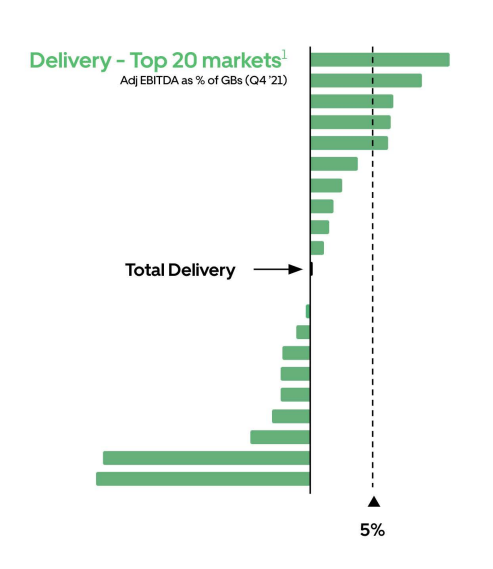

Though it is difficult in the beginning, there are many countries around the world where food delivery 2.0 marketplace economics are proven to be just as profitable as food delivery 1.0 marketplace orders. EBITDA as a percentage of GMV (or gross bookings to use Ubers terminology) in the long run will reach 5-8% just as it has for food delivery 1.0 marketplaces.

In Ubers most profitable delivery markets EBITDA as a % of GMV is above their 5% target.

Source: 2022 Uber Investor Day Presentation

Returning to the important question of “Will leading food delivery businesses ever be valuable free cash flow generative companies”, for Food Delivery 2.0 marketplaces we believe that question has been answered.

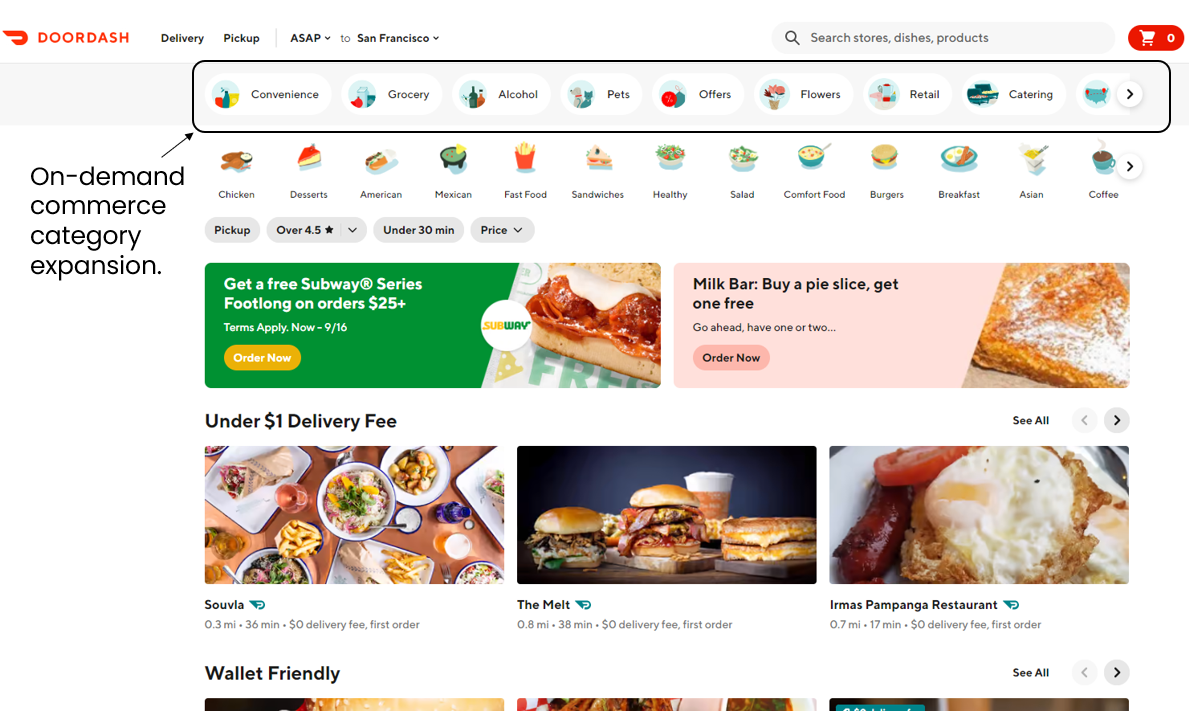

In 2018-2019 the food delivery industry started going through another shift where players around the world were increasingly talking about leveraging their driver fleet to deliver more than just restaurant food, but convenience items, grocery, and anything a consumer wants on-demand. This sparked the birth of the food delivery 3.0 era.

Food Delivery 3.0: Food delivery marketplaces are becoming on-demand marketplaces.

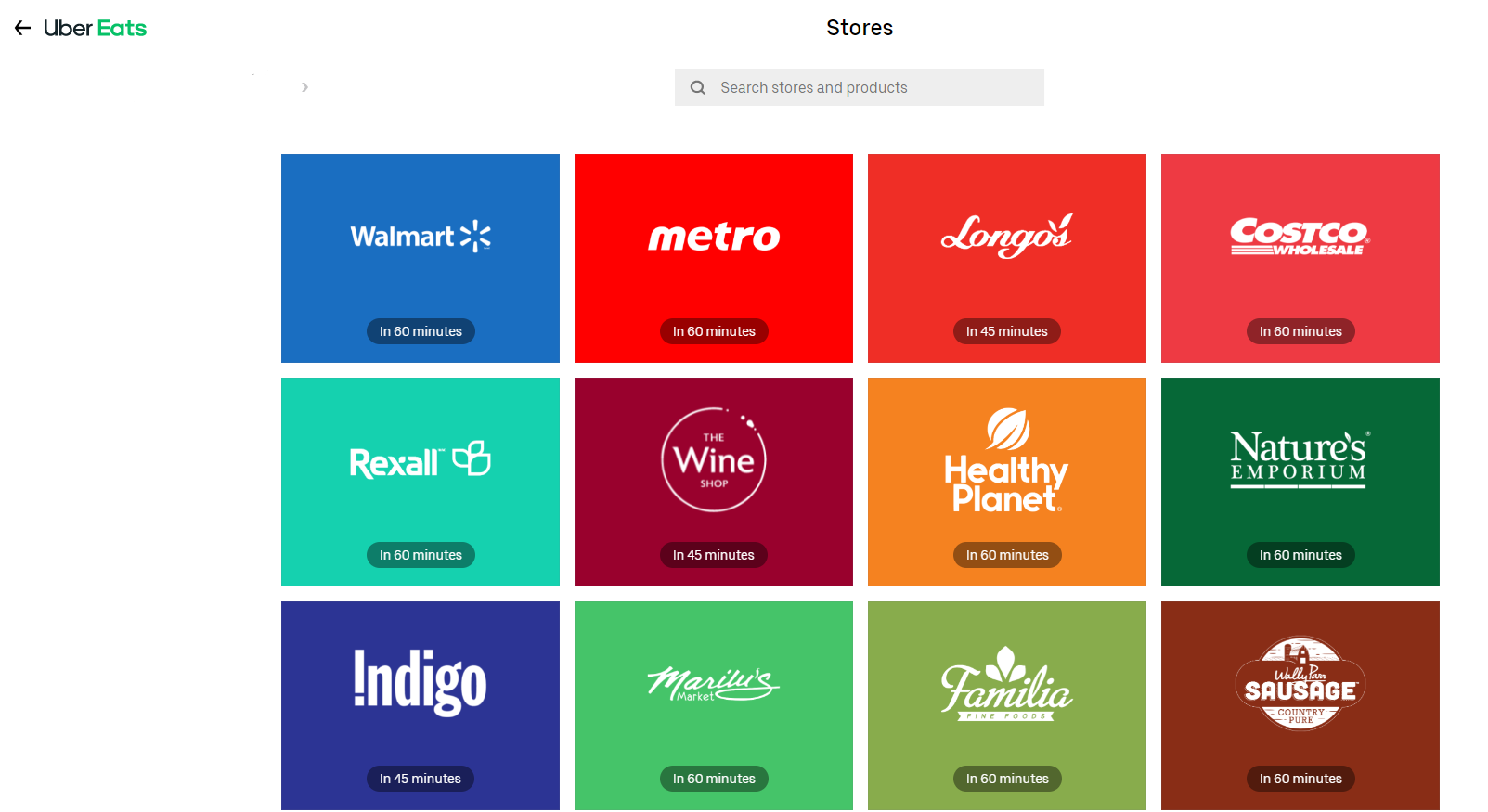

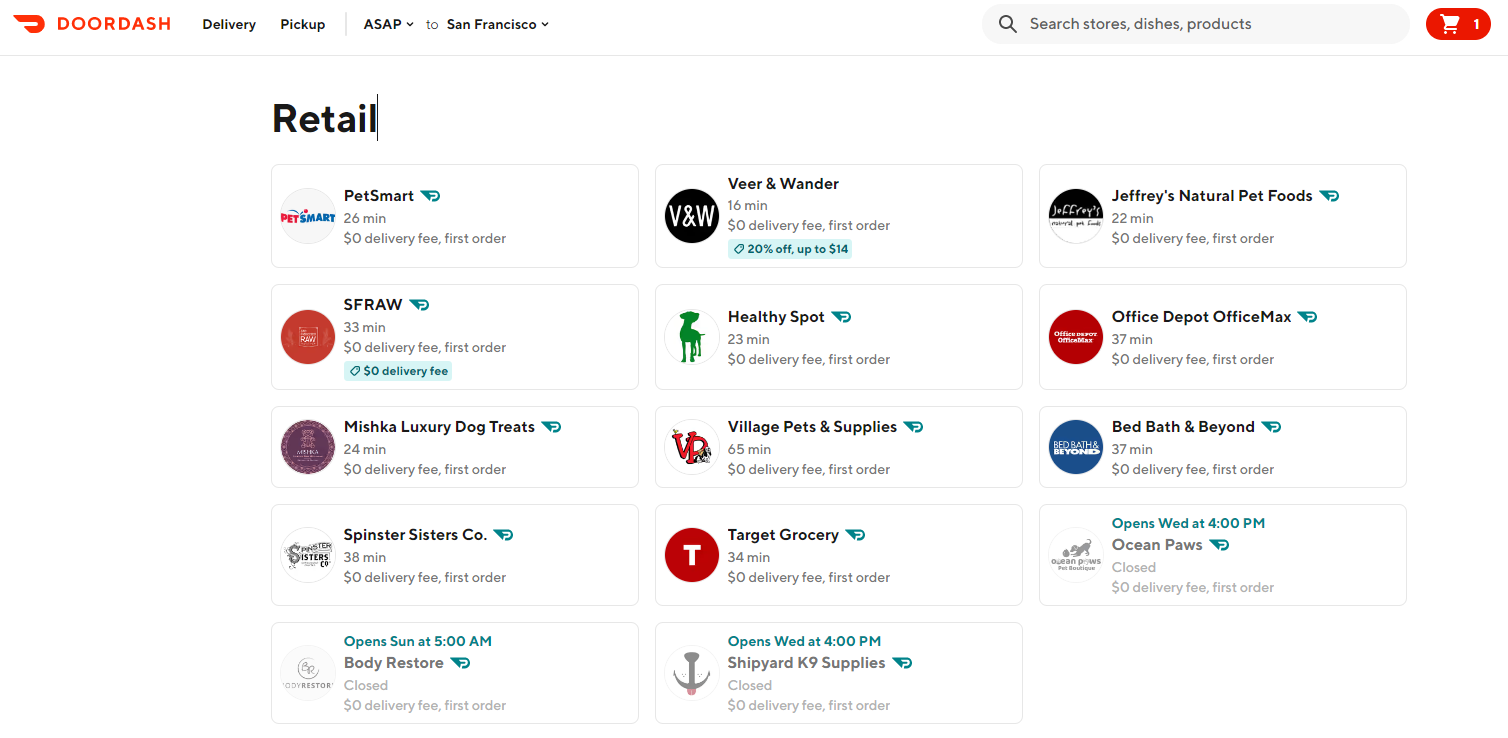

Now that all food delivery 1.0 marketplaces have became a hybrid between a food delivery 1.0 and 2.0 marketplace, the 2.0 marketplaces pushed the industry to phase 3.0, delivering anything on-demand.

Amazon started with books in 1995, expanded to CD’s in 1998 and by 2000 was selling toys, electronics and other retail categories. The food delivery market is going through a similar evolution from restaurant food delivery to an on-demand marketplace delivering anything you want in less than a few hours.

The network of drivers that food delivery players possess has allowed them to expand into delivering more than just restaurant meals. Convenience and grocery store items have been the most meaningful area of expansion thus far but we believe we are in the early innings of category expansion. As more merchants want to offer 1 hour delivery as an option to differentiate themselves against Amazon, more will do so through partnering with a company with a last mile delivery network such as Doordash or Uber Eats.

On-demand last mile logistics networks can enhance brick and mortar retailers key competitive advantage.

Today the value of a brick and mortar retail store is typically viewed as the in store shopping experience, i.e. physically seeing the product before you buy it. Though seeing the item before you buy it can be advantageous, a considerable portion of brick and mortar sales occur because they are in fact more convenient. E-commerce players love to talk about how shopping an endless selection of products from the comfort of your own couch is the most convenient form of shopping but they fail to talk about the scenarios when you need the product immediately.

If you need parts or supplies to fix something today, driving to Home Depot immediately is often the most convenient option. If Amazon does not offer delivery within the next 1 hour, they can’t address your current need.

So you jump in your car, drive over to the store buy the item and in about an hour the mission is accomplished. You spend 1 hour doing the logistical component of getting to the store, finding the product, buying the product and driving home. This process probably took 55 more minutes to complete than if you bought it on Amazon, but at least you have the product at your house in an hour versus tomorrow or later.

Brick and mortar stores have a material competitive advantage against Amazon in one key area. Their inventory is closer to the customer which enables the customer to get the product sooner.

More retailers are picking up on this and partnering with last mile logistics networks like Doordash and Uber to offer delivery within a few hours. We expect this trend to continue.

Over time, increased last mile network density will result in lower prices charged to consumers. In theory, if Uber and Doordash could connect all local retail to their last mile delivery network than every local business could locally out compete Amazon online from a convenience standpoint.

We believe on-demand last mile delivery networks will significantly grow in value over the next decade and unlock many adjacent opportunities.

The economics of food delivery 3.0 are no different than food delivery 2.0 orders.

The economics of food delivery 3.0 orders are structurally no different than the economics of food delivery 2.0 orders, but being in the early innings of category expansion likely means the orders today are less profitable. Today many retailers are getting a discounted commission rate to encourage joining the network. Doordash, Uber Eats and other food delivery companies need to create the consumer habit of buying more categories on-demand which is only possible if they have the selection of retailer’s consumers want.

In our opinion, the long-term profitability of on-demand non-food orders is not a question, it is what percentage of consumers value 1 hour delivery if they have to pay a few dollars more for it. Time will tell.

One major question remains to know if the size of the prize is worth the fight.

Now that we have concluded that leading food delivery businesses can be valuable free cash flow generative companies, how valuable could these market leaders become?

This is a question we will answer in part three of our three part series "“The Global Food Fight”.

The Global Food Fight: Is the Size of the Prize Worth the Fight? (Part 1/3)

Over the last 10 years, arguably the biggest development in the global restaurant industry has been the growth of food delivery companies such as Uber Eats, Doordash, Delivery Hero, and Just Eat Takeaway.

Source: Company Filings

“GMV”: Gross merchandise volume (millions)

“CAGR”: Compounded annual growth rate

The growth has been impressive, but it was achieved while producing over $5 billion in cumulative operating losses.

The significant operating losses spark two important questions:

Will leading food delivery businesses be valuable free cash flow generative companies? If so, how valuable could the industry leaders become?

Over the last two decades, the food delivery industry has had several phases that we describe as food delivery 1.0, 2.0 and 3.0. To answer the important two questions above, we must dig deeper into the three phases of industry development starting with food delivery 1.0.

Food Delivery 1.0: Food delivery has been around for decades.

It is often perceived that the food delivery industry is new because of the significant growth of DoorDash and Uber Eats, but in fact, many restaurants have been offering delivery for over 50 years.

Before restaurant delivery websites were invented in the late 90’s and early 2000’s, when you wanted to order in, it was pizza, Chinese, or another local independent restaurant. There weren’t that many options. Delivery restaurants would market their phone number in the yellow pages and their employee’s would deliver the food. When they delivered your meal, they would leave you with a paper menu in hopes that you became a recurring customer. The telephone is what enabled food delivery restaurants to exist.

Below are some of the most common food types that have been delivered for decades.

Source: YouGov

Converting phone orders to internet orders.

When the internet became increasingly popular in the late 90’s and early 2000’s, several companies developed websites where delivery restaurants could post their menus and receive orders online. Delivery restaurant marketplaces were two-sided networks, connecting consumers and delivery restaurants. This is how Just Eat Takeaway, Grubhub, and Delivery Hero’s business started and is what we will call “food delivery 1.0 marketplaces”.

Source: https://www.uncorkd.biz/blog/restaurant-apps/grubhub-food-delivery-app/

The centralized one-stop shop for delivery restaurants dramatically improved the shopping experience. When more consumers ordered from a food delivery marketplace, more economic opportunity was created for delivery restaurants. More economic opportunity for restaurants then fueled more restaurants to join the marketplace which drove more consumers to use the marketplace and hence, a flywheel was formed.

The flywheel, that is often described as network effects, drove concentrated food delivery market structures where typically one player controlled more than half of the market in a given country. Whoever had the widest supply of delivery restaurants and the highest brand awareness won.

The growth of food delivery 1.0 marketplaces was driven by simply converting phone orders to digital orders and by increasing consumer awareness of the local restaurant options that already offered delivery.

The order economics for food delivery 1.0 marketplaces are attractive.

Food delivery 1.0 marketplace’s charge a commission on orders placed through their website. The incremental costs to the marketplace for an incremental order is website hosting, payment processing, and customer support. Since the delivery restaurant is the one handling the delivery, the operational complexity for a food delivery 1.0 marketplace is minimal.

Source: Company Filings, Optimist Fund Estimates

The unit economics are uniquely attractive.

The unit economics of a food delivery business is contribution profit per order multiplied by the number of orders placed over the lifetime of a customer compared against the cost to acquire a customer.

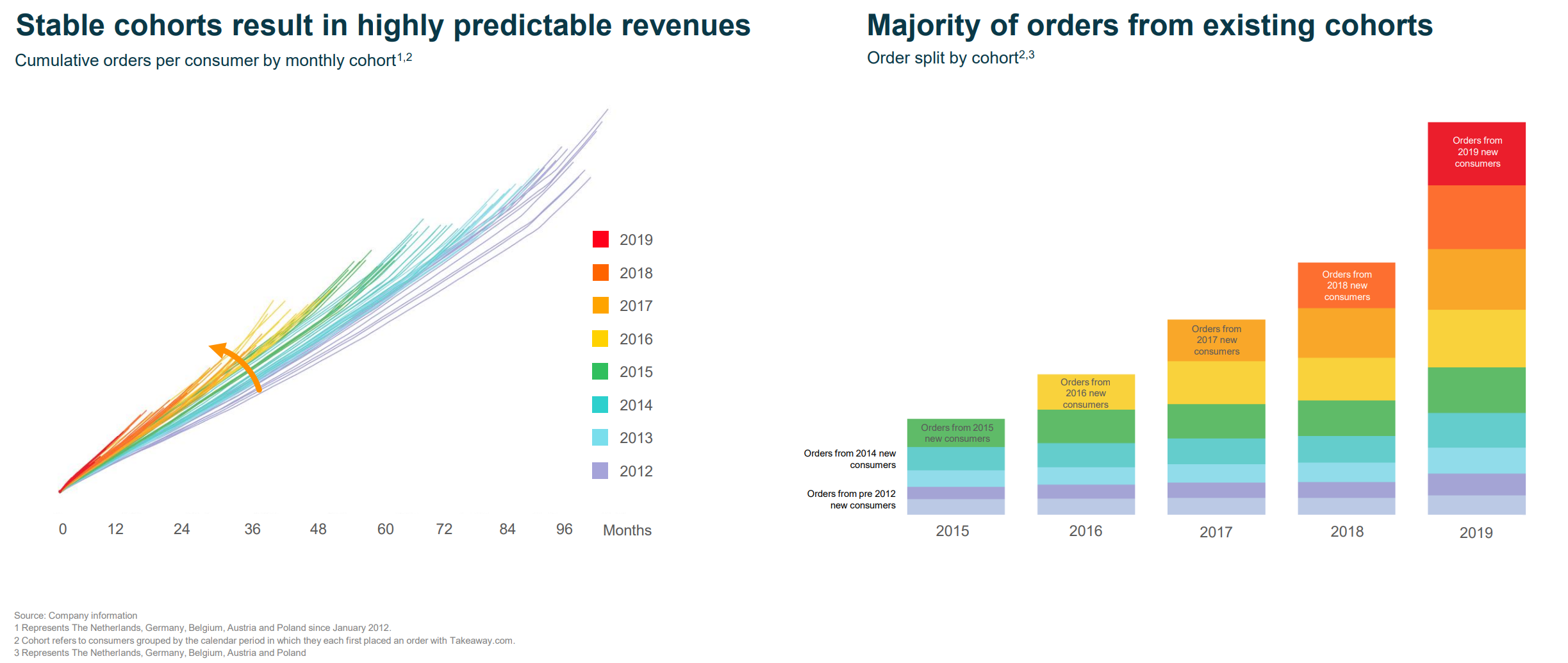

Food delivery 1.0 marketplaces have attractive customer economics due to the high levels of customer retention and repeat usage. Once a customer uses a food delivery platform, they typically use it more and more as time goes on. The consistent annual growth of customer cohorts profit contribution is unique for e-commerce companies where typically new customers spend 50% less in year 2 as they did in year 1.

Source: Takeaway.com FY2019 Analyst Presentation

Grubhub, Delivery Hero, and Just Eat Takeaway, in general, had a 1-year payback on customer acquisition spend. For every dollar spent on advertising, food delivery 1.0 marketplaces would earn $1 dollar in contribution profit in the first year. After the first year, consumer cohorts would continue to generate at least $1 dollar of contribution profit annually. Today the companies have cohorts that are over 10 years old that continue to grow. In other words, $1 invested to acquire customers has returned over $10 dollars in contribution profit over the life of their oldest cohorts. These are highly attractive customer economics.

The strong unit economics of food delivery 1.0 marketplaces eventually drove robust consolidated financial results evidenced by Just Eat Takeaway’s Netherlands business which used to generate over 50% EBITDA margins and 8% margins as a percentage of gross merchandise volume.

Just Eat Takeaway’s Netherlands business was the blueprint of a successful food delivery 1.0 marketplace.

Source: Takeaway.com 2018 Analyst Presentation

To the original question “Will leading food delivery businesses be valuable free cash flow generative companies?”, for Food Delivery 1.0 marketplaces the answer is a resounding yes. Just Eat Takeaway’s UK, Netherlands and German businesses, Grubhub’s US business, and many other markets have generated EBITDA margins of 5-8% of GMV which translates into 4-6% free cash flow margins.

A shift in the food delivery market was beginning to emerge.

In the 2011-2015 time period food delivery companies like DoorDash, Postmates and Deliveroo (based in the UK) were founded to provide delivery for restaurants that did not deliver. As these companies grew in popularity, questions began to emerge as to what impact this would have on food delivery 1.0 marketplaces.

“They aren’t competing with us” several food delivery 1.0 marketplace executives would say. They weren’t lying. For example, Deliveroo in London was focused on providing delivery for higher end dine-in restaurants that would never be viewed as competition to the cheap delivery restaurants you would find on Just Eat’s marketplace. The restaurant selection was fundamentally different.

But if a consumer in Manhattan, who orders Chinese food from a food delivery 1.0 marketplace every Friday decides to switch it up and order from Appleby’s on Uber Eats, all of a sudden that creates a new competitive alternative.

The competitive dynamics of the industry were beginning to change and the establishment of the food delivery 2.0 era emerged.

This was part one of our three part series “The Global Food Fight”. Subscribe to our updates and letters below to be notified when part two, Food Delivery 2.0 is released.